During the recent Joint Finance-Appropriation Committee fall review, a segment was devoted to a post-mortem of the troubled $200 million plus state Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, known as Luma. As it turns out, Luma is going to be a net loss for Idaho taxpayers.

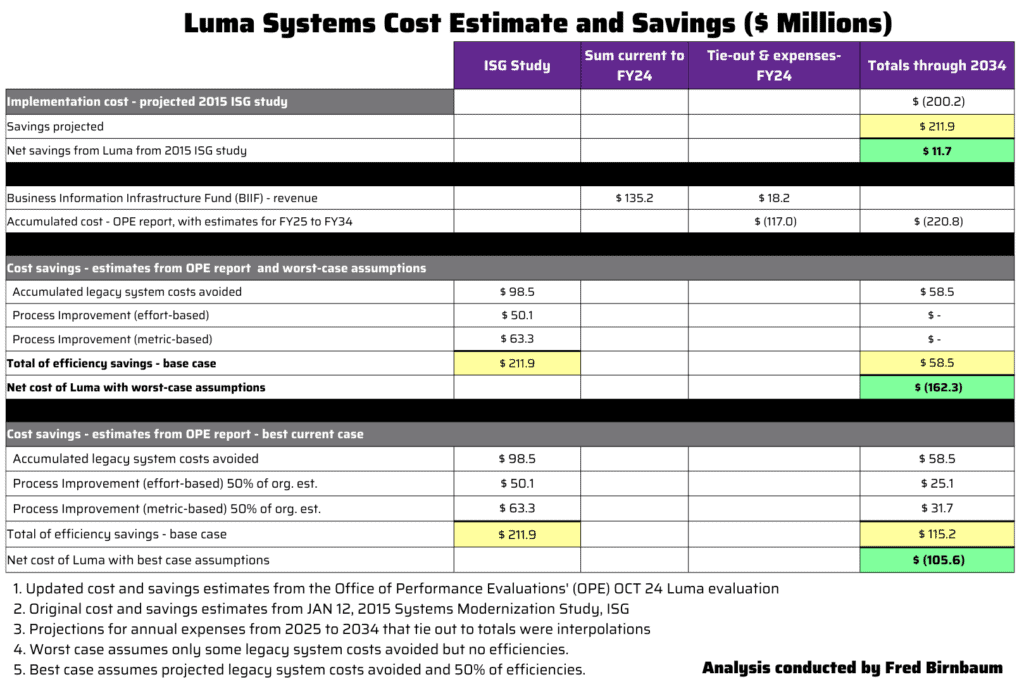

While a reasonably thorough report was issued by the Office of Performance Evaluation (OPE) detailing many of the problems with the roll-out, what wasn’t made clear was how unrealistic the project was from the get-go. The financial analysis, which was based on the original 2015 study, and the provision of only one alternative should have been a red flag. As it turns out, Luma, which was sold as being a cost-neutral upgrade to Idaho’s legacy administrative systems, will have a net cost of over $106 million and perhaps as high as $162 million by 2034 –- the end of the study period. This issue is far more significant than the $14.5 million delayed payment to property taxpayers due to reporting delays, as others have reported. The $14.5 million can be paid out a year later, but the money lost due to the inefficiencies with Luma is gone forever.

The original 2015 study was conducted by the Information Services Group, an advisory and consulting firm, analyzing Idaho’s administrative services systems. These systems provide financial management, procurement, and human resources/payroll functions for the state government. As noted in their study in the Executive Overview:

“For purposes of this study, the State has assumed that the replacement system will be a potential/hypothetical statewide Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system. An ERP system is a suite of fully integrated software applications that perform administrative business functions such as accounting, procurement, human resources, and payroll. Such an initiative would not only replace central systems, such as the Statewide Accounting and Reporting System (STARS) and the Employee Information System (EIS), but also replace a significant number of other central and agency specific administrative systems. Furthermore, ERP systems typically offer additional functionality that would expand system capabilities beyond what is presently available to a majority of State agencies.”

The report also contained a very important caveat as follows:

“Note that the financial analysis of this study is based on a hypothetical ERP implementation timeline that is very aggressive and optimistic.”

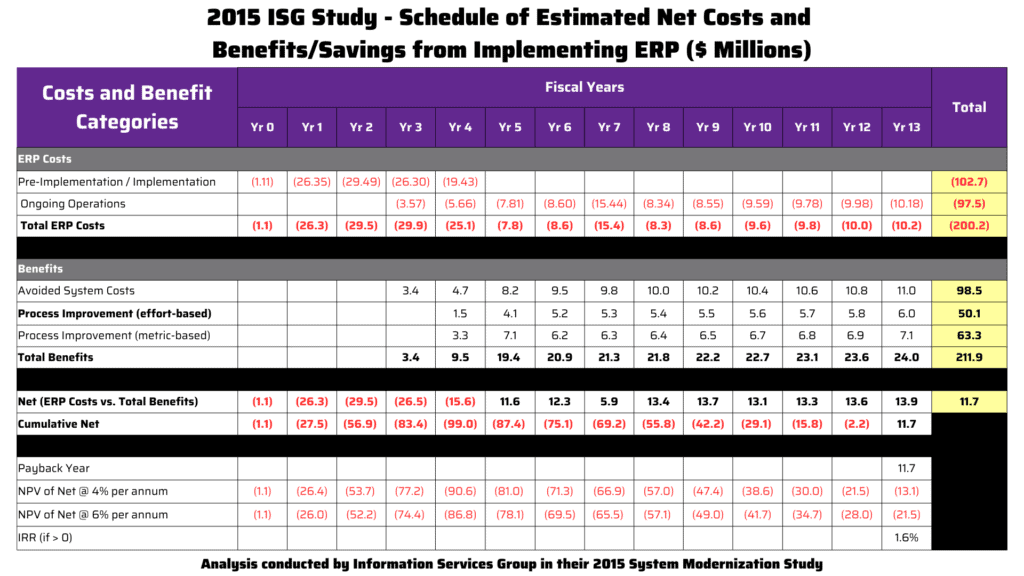

Yet even with that caveat, the study proposed a $102.7 million initial investment and $97.5 million of ongoing costs for a total project cost of $202.2 million over 13 years. Balanced against those costs were savings of $211.9 million accumulated over the same time. It would take until year 13 to reach break-even under “very aggressive and optimistic” assumptions.

The savings were to be achieved by avoiding the costs of maintaining the old system and other efficiencies and cost savings related to process improvement. The process improvement components were to capture $113.4 million in savings. So, $202.2 million of costs to produce $211.9 million in savings. Close to cost-neutral.

In fact, in defending their position on the financial outcome, the State Controller’s Office (SCO) has this to say:

“We want to reiterate that the decision to acquire and implement a new ERP system for the state was never based on cost savings. There were legacy system costs that would be avoided because of Luma replacing them, it was always presented as a cost neutral proposition.”

But this response had two main problems. First, the system will not be cost-neutral but cost-negative. Secondly, the sophistry in distinguishing between cost avoidance and cost savings doesn’t hold water. Cost avoidance was related to avoiding costs associated with maintaining the old legacy systems. Cost savings were related to process improvements or efficiencies with the new system for things such as procurement.

It is a very simple formula: add what was invested in implementing the new system to what it will cost to operate, then subtract the sum of costs avoided from the old system and efficiency savings.

In contrast, the OPE report detailed the following issues with measures for cost savings:

The OPE’s findings suggest a possible worst-case outcome with no cost savings from efficiency when switching to Luma. At best, we could only expect 50% of those savings in efficiency, systems, and process improvements. Ultimately, Luma will cost Idaho taxpayers between $106 and $162 million — despite being sold as cost-neutral (or even slightly positive).

The OPE details recommendations for getting Luma back on track, and we won’t review those here. We agree that it does not make sense to either scrap Luma and return to the legacy systems or scrap Luma and leapfrog to an entirely new ERP platform. It’s time for the problem-resolution mode to kick into high gear.

The real lessons learned are contained in the opening backgrounder in the OPE report, “Large-scale IT implementations are difficult to execute. According to 18F, a federal agency specializing in government software implementation, only 13 percent of large government IT projects succeed.”

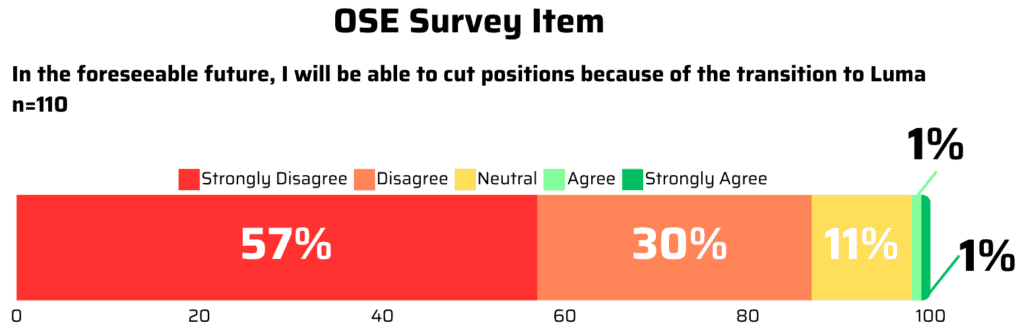

This is further echoed in a survey conducted among several directors and fiscal officers who worked within Luma. Not only did 87% of respondents not see any potential in cutting positions, but 28% had to hire additional employees to deal with the increased workload.

But there is another lesson to be learned here. The notion of efficiency, as commonly understood as producing tangible cost savings, should not be applied to large government IT projects. The accountability isn’t there, and the headcount reductions and cost savings related to actual productivity gains are elusive. While the legacy systems were reaching the end of their lifespan based on the use of COBOL computer language and mainframe computers, the ISG report’s financial projections should have caused those reviewing the recommendations to hit the pause button. More than one alternative should have been considered.

The taxpayers of Idaho are really the ones left holding the bag when it comes to big projects, programs, and initiatives that fail to meet the stated objectives. They ultimately bear the cost of these failures, not the folks at the Capitol. Luma needs an overhaul, and fast, before the taxpayers are hurt anymore.